“Feel Good” Practice vs. “Get Good” Practice (A Rant About Reps)

Why unopposed practice and prescribed mechanics and fundamentals are holding your athletes back

To begin, a universally-understood fact of life: if you do something again and again, you will become better at it. Playing piano. Spinning a basketball on your finger. Speaking in front of audiences. Baking bread. Tying your shoe. Regardless of the specific act, human beings naturally and innately become more fluid, knowledgeable, and proficient at skills/actions they are repeatedly exposed to - even if they are merely doing so for recreation, or out of necessity. Renowned author Malcolm Gladwell surmised in his book “Outliers” that devoting 10,000 hours to a specific skill would lead to “mastery” of that motion, skill or discipline. Gladwell’s hypothesis (which is made, notably, without any empirical proof - even today) is based on conclusions made by recognized psychologist Anders Ericsson, and emphasizes the idea that deliberate and persistent practice is the key to skill acquisition. All this, of course, to buttress the idea that repetition is the key to attainment and comprehension. After all; “repetition is the mother of all learning”. However, a coach who has dedicated time to learning the principles and understandings of ecological dynamics and the Constraints-Led Approach (CLA) may understand that repetition alone does not equate to broad, undeniable success.

Would it amaze you to learn that 18 year old young men are drafted into the National Basketball Association every year who take the jobs of individuals five, ten, or fifteen years their senior - and are the same general sizes & levels of physical capabilities? Haven’t those older players had more time to carve out 10,000+ hours of deliberate repetition - and thus, should be better players? Why isn’t every 12th-grade football player in the United States better than every 9th-grade football player? Haven’t they had more time to familiarize themselves with their own proverbial “toolbox” of skills and mechanics? Can we really attribute the shortcomings of older, more experienced players simply to being less “talented” than a younger player who is more effective? And if so, does this not then open Pandora’s Box into the impossibly deep question of what “talent” is, and how it can be nurtured or instilled into the next generation of humans, purposefully? Not all repetition is created equal. Mr. Gladwell posits that “deliberate” repetition is the most effective method of acquiring skill - but I argue that even deliberate, well-intentioned practice may not be preparing your athletes for the demands of their respective sport, contest, or discipline. Luckily, mindful and inquisitive individuals have been attempting to understand sport, and it’s demands, for us.

Sport is inherently ugly. It is a twisted, writhing, struggle for success. It is unpredictable - jolting, jostling, and chaotic. It waxes and wanes, speeds up and slows down, and, depending on the sport, features vast amounts of room for creativity, expression, and problem-solving. Some, more than others, of course. Every snap of an American football game is essentially a skirmish - a simulation of war. Pads pop, voices grunt, and will battles against will, hundreds of times. In the word of Alex Sarama, Director of Player Development for the NBA’s Cleveland Cavaliers, “sport is much more jazz than it is classical” - it is not the routine march of specific steps and perfectly timed queues, unopposed and predictable, but instead it is the turbulent and disorganized helter-skelter of opponents who are each attempting to be as difficult to compete against as possible. Why then, are players being taught to excel at playing jazz, by using classical music? I explain further (in the context of what I know best - the game of lacrosse):

A bag of balls. Players standing 10 yards apart, feet set, passing the ball across to each other. A coach stopping the drill to explain the proper passing technique, then allowing time for the players to attempt to emulate the “ideal” technique. No meaningful communication - at least not naturally occurring. The coach stops the drill again, this time to direct the players to use their “off (weak) hand”. Drill continues.

Two lines of players. A goal without a goaltender in it. The front of one line passes the front of the other. The recipient of the pass takes a step, and shoots into the open goal - then the reverse occurs - one line passes to another, and step-down shots are repeatedly taken into an empty net. The coach directs attention to the angle of the elbow in relation to the target, proper follow-through technique, and aiming for the “pipes” of the goal - hopefully the far one, if possible. One player shoots. Then the next. Then the next.

Cones are set out in a zig-zagging formation. Players have a ball in their stick. They are directed to “split-dodge” (exchanging which hand is at the throat of the stick while also changing directions - similar to a wide receiver’s release from the line of scrimmage) at each cone. The coach explains how he’d like the player to exchange their hands, and how he’d like them to drive to the next cone, to create separation from their defender. The players go through the cones. Once done, the coach explains the next dodge he’d like done - perhaps the “roll-dodge” (a “spin move” equivalent). Players go back through the cones. Repeat.

Coach Casey Wheel offers his opinion:

The drills explained above plague lacrosse, and drills of similar makeup plague other sports - static, predictable, and identical. These drills would be considered, speaking technically, as “blocked practice”: defined loosely as a segment of practice in which a specific and exact behavior or motion is meant to be mirrored, by the letter of the law - with no flexibility or alternative, again and again and again (perhaps in pursuit of Mr. Gladwell’s prized 10,000 hours). The task, as well as the environment, including external stimuli, remain constant, or absent, and do not play significant roles in the completion of the task. Now, understanding human beings and our ability to learn, blocked practice WILL lead to improvement. A lacrosse player will get better at shooting the ball in the drill described above - as a matter of fact, they may be doing extremely well! They may catch the ball every time, and fluidly release the ball, hitting the far corner of the net every time! A coach may ask a player to try to focus on a specific element of their form, or the mechanics of their movement, and the player might be able to immediately implement that feedback into their motion, and achieve success! By no means is blocked practice making players worse at their sport and it’s demands. As a matter of fact, a player and their coach may feel incredibly accomplished by seeing optimal results, and watching the feedback loop (action - critique - refined action) complete itself in a short span of time. However, I would offer that blocked practice is our “classical music”. Preplanned. Exact. Static. Routine. This would be an ideal set of exercises if the sport of lacrosse was played by only one team at a time! The players in this practice certainly have improved - but at what? Shooting the ball on a net with no goaltender? On a field with no defenders? And no score? They’ve gotten better at dodging with the ball - but only if they plan to play in the game against cones (who are known for being poor defenders). Ecological coaching pioneer Drew Carlson offers:

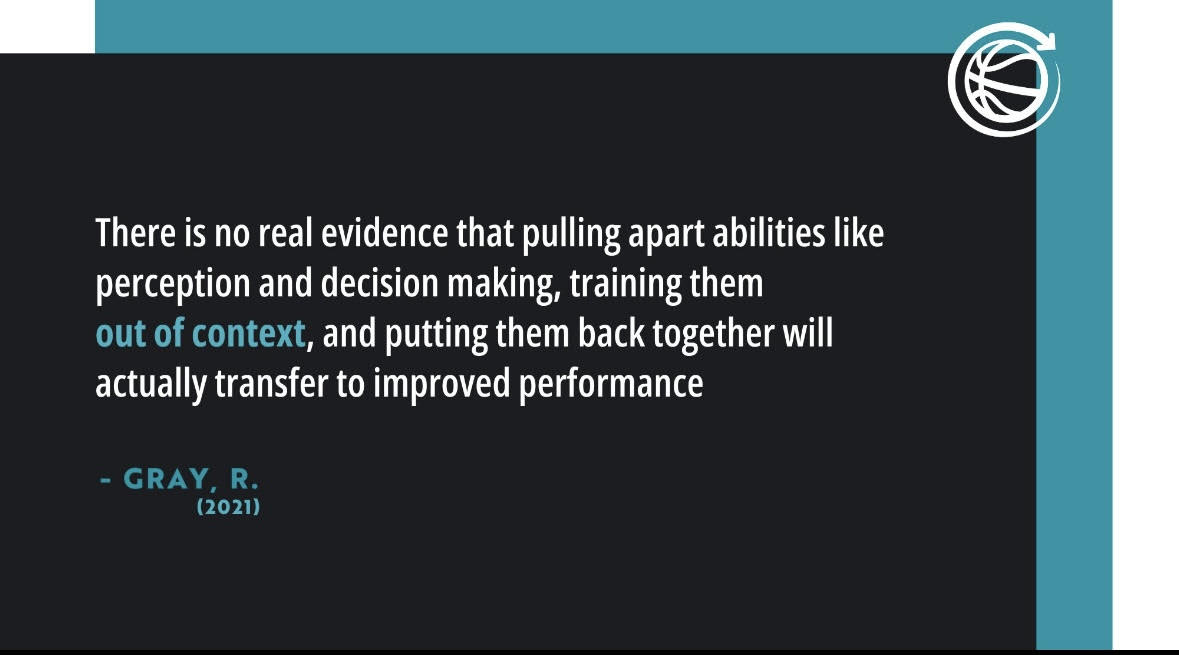

Coaches forget, in many cases, that the game is jazz, not classical - the sport was created to be opponent v. opponent - yet we distance that relationship from our training! To focus entirely on “action” and completely remove the “perception” prior is to strip apart the most essential cognitive process an athlete will ever utilize! Would you teach someone to drive a car, but forget to tell them that other cars also exist on the road? There will ALWAYS be a goaltender trying to take away your angles. There will ALWAYS be a defender (or multiple) trying to ruin your day, and take what’s yours. There will ALWAYS be a score, and ALWAYS be time on the clock. To remove variables is to remove vital information for the players to process. And the sense of accomplishment we feel after having performed so well, or progressed so much in an environment which is OPTIMAL to our success? Fool’s gold, sadly. I’ve taken to calling blocked practice “Feel Good” reps - the illusion of expertise and accomplishment - yet, virtually useless in an unforgiving and unpredictable environment like a true game. I think about Kelvin Sampson of the University of Houston’s Men’s Basketball team, when asked about individual workouts and skills sessions: “If you’re playing in a one on zero tournament, I think you’d be pretty good. The problem is we play five on five”.

Kelvin Sampson on blocked practice - link

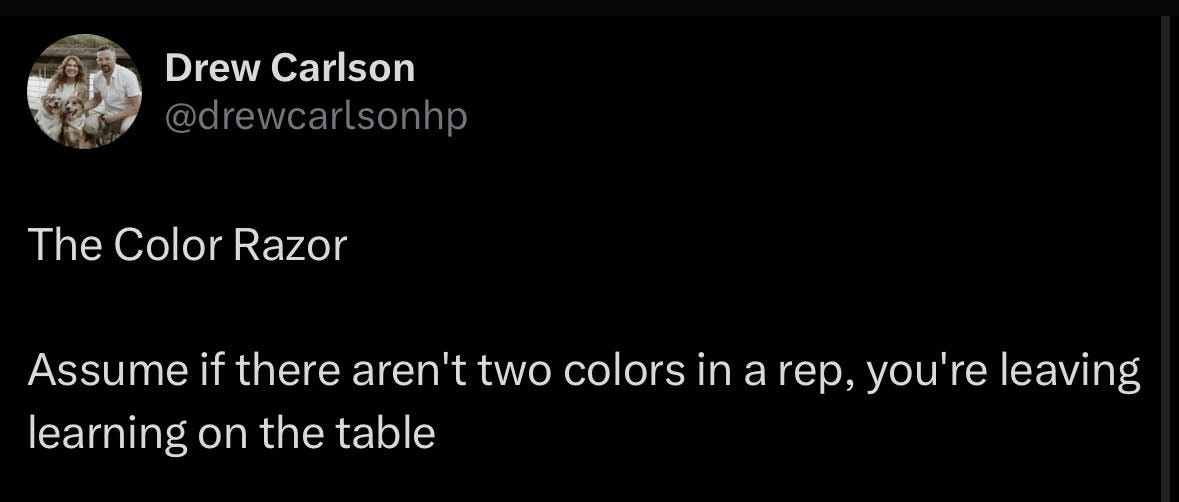

Worth noting: there is a time and a place for Feel Good reps! There is a benefit to players seeing and feeling what a movement could or should feel like - an environment devoid of stimuli and opposition can be useful for exploration of movement possibilities. However, to coach a team and to prepare athletes utilizing exclusively blocked practice is to send them into the game with one hand tied behind their back. They’ve learned how to climb a mountain - but weren’t prepared for the driving wind, and the freezing rain, and the slippery surfaces that mountains innately may feature - they’ve learned the “how”, but have been left without the “what”. However, a good rule of thumb to consider when designing a drill, or a practice: if at any point the player can routinely do something mindlessly, the drill or practice is leaving learning on the table. If you plan on teaching a technique or form in a vacuum, and then teaching it while in a live-game setting, I would posit that your precious practice time could be used better attempting to kill far more birds, with far less stones.

Jamie Munro, former coach of the University of Denver Pioneers’ Men’s Lacrosse team, as well as professional lacrosse coach, and trailblazer of the ecological dynamics movement in lacrosse, on his podcast, the Ecological Lacrosse Podcast, went as far as to say “If you are teaching players how to do something on air that they’ll have to re-learn to do against opponents - why even teach them do so against air at all?”. We remember, of course, that sport is ugly. If we, as coaches, have our players’ best interests at heart, we would work to make sure our practices best replicate the demands and requirements of the game they’ll be playing in! A drivers’ test is not done on a closed course with no other vehicles around, because that’s not what the demands of driving a car when it truly counts would require. We expose and assess new drivers to realistic and variable environments, so they may be adapted to that type of setting - removing the “fog of war”, or the unpredictability of a world populated by sporadic individuals, means success is more likely to come, but ONLY in the carefully-curated world you’ve created for them. When we allow our players to hear jazz, they’ll be better adapted to playing jazz. Drew Carlson adds:

When players are required to actively assess their environment, identify affordances and constraints, and attune to the different agents acting around them and upon them, they’ll be much more prepared to do so during a genuine game. Doing so is known as “random practice”. Random practice is best described as allowing players the freedom to interact with their environment as they see fit - removing subscriptive answers, adding situations to interpret, and connecting perception with action once again. Luckily, random practice is a sibling of blocked practice - not a long lost cousin. It can be easy to shift from one kind of practice to another!

Instead of stagnant partner passing, create a “keep-away” style game (called a “Rondo” to those in the soccer/football world), which gives players the chance to react to defensive coverages, move their feet, create unique and in-real-time solutions to unorthodox situations and problems, and communicate in a meaningful way.

Instead of simple, mindless (and boring!) “pass-and-shoot” routines, simply prompt players by saying “score in a different way every single time!” or “play like your favorite player would play!” - we can even turn those who JUST shot the ball into impromptu “defenders” for the next player through the drill, as they return to the top of the drill - and we can give these defenders different prompts, too! For instance, in lacrosse, we can tell our faux defenders to approach the ball differently each time, or to throw a different kind of stick check each time they approach the ball - any drill is a thousand drills, all we have to do as coaches is put a new wrinkle into play, or place a new intention into the players’ minds. 1 vs. 1. 1 vs. 2. 2 vs. 2. 3 vs. 2. 3 vs. 3. Etcetera - if you have an entire group of athletes who all play the same sport together, what is the logical argument against putting them together? When a coach is able to remove himself/herself from the “overseer” position, and is able to prevent “joysticking” players around the field, and around their own motor functions, optimal solutions, mental stimulation, and joy emerge.

I have taken to calling these representative drills and games “Get Good” reps - chocked full of real-time decisions to make, defenders to approach and operate around, and movements or skills to try and observe the results of. Coach Jamie Munro has taken to calling this philosophy “bones over cones” - the idea that “Get Good” reps serve a player better in the long-term than “Feel Good” reps do - highlighting self-organisation in athletes - allowing them to find their own chosen ideal solution to a problem - even if they don’t do so successfully.

This is, of course, the foundation of ecological dynamics and the “Constraints-Led Approach” - a perspective on coaching which empowers players to find their own solutions, and to prop up the cycle of perception and action, so players become adaptable and independent problem solvers. A coach who takes the CLA to it’s extreme may leave ALL “on-air” drills behind, and focus explicitly on small-sided games (SSGs), scrimmages, and competition in practice - adding in layers of complexity and various constraints which allow for different problems and scenarios to occur. A coach who is tentative to fully implement the CLA may start just by adding the perception component to their historically “on-air” drills, as I’ve described above. Regardless of the level of dedication a coach has to the idea of ecological dynamics and the CLA, any coach who has their players’ best interests at heart should look to replicate the game as best they possibly can - that starts with representative practice design and opposed practice, as much as possible. It has become commonplace to pare down the “part-whole” idea too far - dissecting a situation or skill into bland, repeated, prescribed motion again and again (“Feel Good” practice) - solutions become more dogmatic and universal than open-ended and interpretable. Dr. Rob Gray at Arizona State University goes as far as to say:

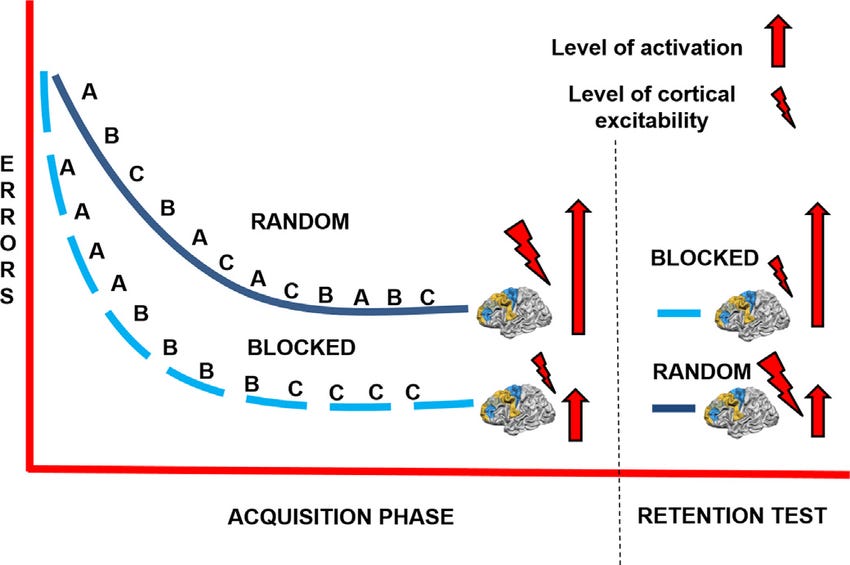

Sport, we know, is ugly. If we incorporate more (or explicitly) “Get Good” reps in our practices, those drills and games, naturally, will be ugly as well. Mistakes, trials and errors, attempts and understanding, and insecurity are all possible - and likely. As a coach, this can seem daunting - we all want our practices to flow smoothly. We want technique to look polished. We want the offense to score, and the defense to prevent scoring. “Am I really coaching if I watch as my players fail, and do not change the environment, or offer the answer immediately so they may see success? am I really still coaching, if the feedback loop is delayed - or I’m even removed from it altogether?” Yes! Data has shown that players who experience random practice (“Get Good” practice) significantly improved retention over those who experienced blocked practice (“Feel Good” practice) as it pertains to the acquisition and mastery of motor skills and locomotive freedom.

The model below, curated and provided by Dr. Guilherme Lage and his co-authors in their 2015 journal “Repetition and variation in motor practice: a review of neural correlates”, illustrates how individuals who encounter random practice display significantly more errors during the “acquisition phase” (practice) as well as a higher levels of neural activation - far more thinking - than those who encounter blocked practice. However, during the “retention test” (a game/contest/match), those who learned through blocked practice displayed more errors, and more neural activation than those who learned through random practice - that group displayed less errors, and less neural activation during competition. Allowing the game to be the teacher is not negligence from a coach’s standpoint - the opposite, actually! Embracing ugly early makes pretty play on game day! Perhaps a player is taking less shots, or encountering a scenario fewer times during a practice if the coach is utilizing SSGs, scrimmages and competitions - but if the learning from those limited encounters with the situation actually manifest themselves better during competition, wouldn’t we prefer less reps of significantly better quality, than more reps of significantly worse quality?

Drs. John Shea and Robyn Morgan support this conclusion in their 1979 journal “Contextual interference effects on the acquisition, retention, and transfer of a motor skill”:

“Interleaved [random] practice has more contextual interference than repetitive practice - resulting in a slower initial rate of skill acquisition however it will support a superior long-term retention”

The occupation of a “coach” is notoriously open to interpretation. There is no universal set of bylaws, purposes, prerogatives, and protocols. Legendary football coach Pete Carroll is quoted as saying:

“What if my job as a coach isn’t so much to force or coerce performance as it is to create situations where players develop the confidence to set their talents free and pursue their potential to it’s full extent?”

NBA Champion coach Steve Kerr offers:

“The urge is, you’re the coach and you want to control it. But, coaching isn’t controlling it, it’s guiding it. It’s not going to happen by you saying ‘you have to do this or you have to do that.’”

If you’re feeling brave - or feeling like your players have two different sets of skills: things they can do in practice, and things they can do in games - I implore you to offer a heightened significance upon “Get Good” practice, and to leave “Feel Good” practice behind, as much as possible. Each sport has it’s own nuance and nature, so to do so looks incredibly different on a case-by-case basis, but beyond the scope of specific sports: representative design, opposed practice, and the connection of the perception-action circuit is vital to creating adaptable and competent problem-solving athletes. Consider Drew Carlson’s “Color Razor”:

Moreso: when athletes get to compete they have FUN! You cannot help develop a player who doesn’t come back. When you allow individuals to explore their degrees of freedom, and do so with stakes attached, while competing against their peers, you are fostering an environment not only of learning, but of immersion, and enjoyment. Overall? “Feel Good” practice provides the appearance of mastery - “Get Good” practice actually creates it.